There’s a highly infectious illness sweeping through the country at the moment. It’s called DreamWorks Heroes Action Card Fever. Symptoms begin innocently enough with excitement at opening a little packet and pulling out a new card, to disappointment at receiving a duplicate, followed by card swapping at school or organised meets, or even ridiculous bidding wars on Trade Me. If you shop at Countdown, your child has probably been infected and may now be desperate to complete the set of 42 cards.

As far as we know, completing the set is the only cure, but here, we offer some pain relief for parents. You can find plenty of maths in these pretty little cards if you’re sufficiently interested. They can actually help your children to practise their multiplication and division by 6. Also, at any point in the collection, you could ask your children to lay out their cards in a neat rectangular grid. How many ways can they do this? This will get them thinking about factors. For example, a 12 card collection could be laid out in a 3 x 4 grid, a 4 x 3 grid (aha, multiplication is commutative!), a 2 x 6 grid, and so on.

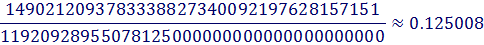

So now your children are doing some maths whilst playing with the cards, but what about us parents? We’ve calculated some probabilities so that, at any point in time, we know (theoretically) how many packets need to be opened to find a new card, and ultimately, how many packets it will take to collect the whole set.

Intuitively, it should make sense to most of us that, the more cards you have, the harder it will be to find a new one. For example, if you have only one card, then the probability that the next packet contains a new card is  = 97.6%. But if you have 41 cards, then the probability that the next packet contains a new card is

= 97.6%. But if you have 41 cards, then the probability that the next packet contains a new card is  = 2.4%.

= 2.4%.

But the big question is, as the collection grows and you encounter more duplicates, just how many packets will you need to open to get a new card?

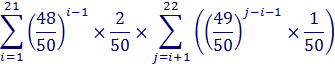

Let’s consider a concrete case. If you have 14 cards in your collection, then there are 28 cards that you don’t have. To calculate the expected number of packets you will have to open to get a new card, we take a weighted sum of probabilities based on the number of packets it might really take.

The probability that the next packet contains a new card is  = 66.7%.

= 66.7%.

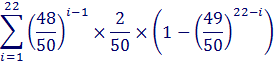

The probability that the next packet contains a duplicate but the following packet contains a new card is  = 22.2%.

= 22.2%.

The probability that the next two packets contain duplicates but the following packet contains a new card is  = 7.4%.

= 7.4%.

As you can see, the probabilities are decreasing quite quickly, so if at this stage in the collection it took, say, five packets to get a new card, you’d be very unlucky since the theoretical probability of this happening is  = 0.8%.

= 0.8%.

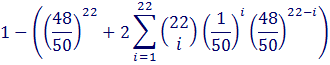

To calculate the expected number of packets that need to be opened to get a new card, we calculate the infinite sum:

What, adding numbers forever?! Well yes, but the good news is that while some sums will grow to infinity, this one doesn’t because the numbers we’re adding are diminishing quickly enough. We actually get a sum that will barely change if we go out far enough. This is what we call convergence.

Fortunately, this type of infinite sum is well-known. It’s an arithmetico-geometric series with sum

So, in theory, with a collection of 14 cards, you would have to open 1.5 packets to get a new card. Of course, this is a nonsense number in the real world, but it does tell us that, up ‘til now, we would have expected every packet you’ve opened to produce a new card, but now, you are on the cusp of encountering your first duplicate card. From here on, it is quite likely that you will have to open at least two packets to get a new card.

This calculation can be generalised so that we know at any point in the collection how many more packets it will take to get a new card. If you have n cards in your collection, the expected number of packets is a delightfully simple expression:

Rounding these expected numbers to the nearest whole number, we can now see how hard it will be to complete the collection, especially near the end:

In summary, assuming Countdown has distributed the cards fairly and you’re not doing swaps all the while, you’re going to need about 180 packets to collect the whole set, amounting to a $3,600 spend (not allowing for bonus promotions). For a six week promotion, that’s $600 per week. Some families might manage that, but we certainly won’t. Instead, we’re simply delighting in how our “simulation” is panning out remarkably closely to the probabilities we’ve calculated, and accepting that the only realistic way to collect a full set is to swap, swap, swap, or go mad on TradeMe. As we write, the highest Buy Now price for a full set is $250. Quite a bargain, when you think about it.

There is another strain of the virus called DreamWorks Heroes Action Card Album Fever, whereby people are willing to pay more than ten times the retail price for a $6 album. We have no expected numbers for that one.

Dr Audrey Tan, Mathmo Consulting

June 2014

= 97.6%. But if you have 41 cards, then the probability that the next packet contains a new card is

= 97.6%. But if you have 41 cards, then the probability that the next packet contains a new card is  = 2.4%.

= 2.4%. = 66.7%.

= 66.7%. = 22.2%.

= 22.2%. = 7.4%.

= 7.4%. = 0.8%.

= 0.8%.