Our “revolutionary” National Certificate(s) of Educational Achievement (NCEA) secondary school qualification, built on ideals of inclusion and equity, has failed to deliver on many fronts.

The New Zealand Initiative has highlighted some serious problems with the NCEA system. Briar Lipson’s well researched report, Spoiled by Choice: How NCEA Hampers Education and What It Needs To Succeed, exposed the harsh reality behind the dramatic growth in numbers of students achieving NCEA Level 2 each year. NCEA performance may be “improving”, but the international survey PISA shows that our 15-year-olds’ capabilities in maths, science and reading are declining.

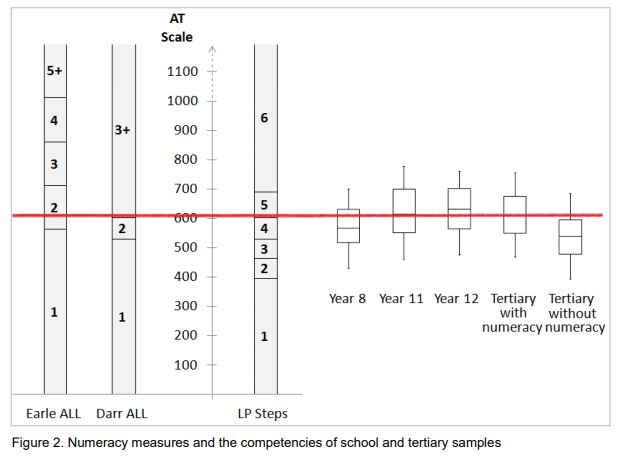

Moreover, despite there being a minimum requirement for literacy and numeracy credits, a Tertiary Education Commission (TEC) study in 2014 found that reasonably large proportions of students with NCEA Level 1 (approximately half) or NCEA Level 2 (four out of 10) were not functionally literate, and similar proportions were not functionally numerate.

So what can we actually ascertain about a student with an NCEA qualification?

Very little, according to the Initiative’s second report, Score! Transforming NCEA Data. It brought to attention the huge variation in grade distribution across subject sub-fields. It is comparatively easier to gain an Excellence grade in Languages and Performing Arts than it is in Mathematics and Statistics. And not surprisingly, they found that more students pass internal assessments than external assessments.

In an attempt to redress these imbalances, the economists at the Initiative came up with a Weighted Relative Performance Index (WRPI) that endeavours to make “sense” of a student’s NCEA credits and provide a fairer comparison of performance between students. 1

It was a laudable attempt. However, one blatant inequity in the NCEA system that was not addressed by the WRPI, and has yet to be discussed widely, is the absence of a sensible time restriction applied to individual external assessments.

Allow me to explain. In Mathematics, students at any of the three NCEA Levels may be entered for a three-hour external examination comprising up to three achievement standards. Each achievement standard is a self-contained assessment/paper, sealed up in its own plastic wrapping. (Biodegradable, I hope.)

It would seem reasonable that each of the three papers should be completed in approximately one hour. 2 Therefore, it would seem reasonable that if a school decides to enter a student for fewer than three achievement standards, then the duration of the exam should be reduced, i.e. one hour for one paper, two hours for two papers. But no, not with NCEA! Schools may enter students for one or two papers, and students still get three hours to complete them!

This obviously puts students entered for three papers at a disadvantage. Are these students supposed to console themselves that they are receiving a better education, even if their peers come out with higher grades because they had more time?

Schools can, and do, game the system by entering their students for fewer than three papers. But students can also game the system by electing to not attempt all of the papers for which they are entered. If they leave the plastic wrapping intact, they will receive a Standard Not Attempted/Assessed (SNA), and apparently this is better than a Not Achieved (N).

Really?? According to this memo, it’s better for schools because School Result Summaries will include N’s but not SNA’s. Also, SNA allows for the possibility that “a student ran out of time so an N would not be a fair result”. In other words, it’s better to fail to try than to try and fail.

For those chasing an Endorsement, it is actually in their best interests to attempt fewer papers and go for higher grades. For example, for a student chasing an Excellence endorsement, two Excellence grades would be preferable to three Merit grades.

Our national secondary school examination system actually rewards students for doing less work.

The acknowledgement of effort is lacking even within an individual paper. In a traditional marking scheme, every correct answer would contribute to the final mark, but NCEA is a standards-based assessment system with “top down” marking. 3 Therefore, confident students can take a gamble and jump straight to the harder parts of a question. It’s a risky strategy, but if it pays off, they may achieve Excellence having answered roughly a third of the paper. This flies in the face of the instruction printed on the cover page: “You should attempt ALL the questions in this booklet.” If you do well, then some of what you do could turn out to be a waste of time.

NCEA is a system that does little to incentivise students to put in maximum effort or to persevere if the results are likely to be sub-optimal. Until these problems are addressed, mediocrity will prevail. We welcome the Ministry of Education’s review of NCEA this year, and hope to be part of that discussion.

Dr Audrey Tan, Mathmo Consulting

21 March 2018

1 Ironically, NZQA in their utopian socialist bubble didn’t want us to compare students, but it’s happening anyway. Students compare themselves, universities have already come up with their own weighted metrics, and employers are learning that “E” grades on a Record of Achievement are actually higher than “A” grades.

2 Prior to 2013, each paper used to start with the recommendation “You are advised to spend 60 minutes answering the questions in this booklet.”, but not any more.

3 Anecdotally, not all markers appear to follow this methodology. Perhaps they too feel that any positive efforts should be acknowledged, even if ultimately ignored in the final score.